Simulation Manual

OMNeT++ version 6.0.3

Chapters

1 Introduction

2 Overview

3 The NED Language

4 Simple Modules

5 Messages and Packets

6 Message Definitions

7 The Simulation Library

8 Graphics and Visualization

9 Building Simulation Programs

10 Configuring Simulations

11 Running Simulations

12 Result Recording and Analysis

13 Eventlog

14 Documenting NED and Messages

15 Testing

16 Parallel Distributed Simulation

17 Customizing and Extending OMNeT++

18 Embedding the Simulation Kernel

19 Appendix A: NED Reference

20 Appendix B: NED Language Grammar

21 Appendix C: NED XML Binding

22 Appendix D: NED Functions

23 Appendix E: Message Definitions Grammar

24 Appendix F: Message Class/Field Properties

25 Appendix G: Display String Tags

26 Appendix H: Figure Definitions

27 Appendix I: Configuration Options

28 Appendix J: Result File Formats

29 Appendix K: Eventlog File Format

30 Appendix L: Python API for Chart Scripts

Table of Contents

1 Introduction

1.1 What Is OMNeT++?

1.2 Organization of This Manual

2 Overview

2.1 Modeling Concepts

2.1.1 Hierarchical Modules

2.1.2 Module Types

2.1.3 Messages, Gates, Links

2.1.4 Modeling of Packet Transmissions

2.1.5 Parameters

2.1.6 Topology Description Method

2.2 Programming the Algorithms

2.3 Using OMNeT++

2.3.1 Building and Running Simulations

2.3.2 What Is in the Distribution

3 The NED Language

3.1 NED Overview

3.2 NED Quickstart

3.2.1 The Network

3.2.2 Introducing a Channel

3.2.3 The App, Routing, and Queue Simple Modules

3.2.4 The Node Compound Module

3.2.5 Putting It Together

3.3 Simple Modules

3.4 Compound Modules

3.5 Channels

3.6 Parameters

3.6.1 Assigning a Value

3.6.2 Expressions

3.6.3 Parameter References

3.6.4 Volatile Parameters

3.6.5 Mutable Parameters

3.6.6 Units

3.6.7 XML Parameters

3.6.8 Object Parameters and Structured Data

3.6.9 Passing a Formula as Parameter

3.7 Gates

3.8 Submodules

3.9 Connections

3.9.1 Channel Specification

3.9.2 Channel Names

3.10 Multiple Connections

3.10.1 Examples

3.10.2 Connection Patterns

3.11 Parametric Submodule and Connection Types

3.11.1 Parametric Submodule Types

3.11.2 Conditional Parametric Submodules

3.11.3 Parametric Connection Types

3.12 Metadata Annotations (Properties)

3.12.1 Property Indices

3.12.2 Data Model

3.12.3 Overriding and Extending Property Values

3.13 Inheritance

3.14 Packages

3.14.1 Overview

3.14.2 Name Resolution, Imports

3.14.3 Name Resolution With "like"

3.14.4 The Default Package

4 Simple Modules

4.1 Simulation Concepts

4.1.1 Discrete Event Simulation

4.1.2 The Event Loop

4.1.3 Events and Event Execution Order in OMNeT++

4.1.4 Simulation Time

4.1.5 FES Implementation

4.2 Components, Simple Modules, Channels

4.3 Defining Simple Module Types

4.3.1 Overview

4.3.2 Constructor

4.3.3 Initialization and Finalization

4.4 Adding Functionality to cSimpleModule

4.4.1 handleMessage()

4.4.2 activity()

4.4.3 Use Modules Instead of Global Variables

4.4.4 Reusing Module Code via Subclassing

4.5 Accessing Module Parameters

4.5.1 Volatile and Non-Volatile Parameters

4.5.2 Changing a Parameter's Value

4.5.3 Further cPar Methods

4.5.4 Object Parameters

4.5.5 handleParameterChange()

4.6 Accessing Gates and Connections

4.6.1 Gate Objects

4.6.2 Connections

4.6.3 The Connection's Channel

4.7 Sending and Receiving Messages

4.7.1 Self-Messages

4.7.2 Sending Messages

4.7.3 Broadcasts and Retransmissions

4.7.4 Delayed Sending

4.7.5 Direct Message Sending

4.7.6 Packet Transmissions

4.7.7 Receiving Messages with activity()

4.8 Channels

4.8.1 Overview

4.8.2 The Channel API

4.8.3 Channel Examples

4.9 Stopping the Simulation

4.9.1 Normal Termination

4.9.2 Raising Errors

4.10 Finite State Machines

4.10.1 Overview

4.11 Navigating the Module Hierarchy

4.11.1 Module Vectors

4.11.2 Component IDs

4.11.3 Walking Up and Down the Module Hierarchy

4.11.4 Finding Modules by Path

4.11.5 Iterating over Submodules

4.11.6 Navigating Connections

4.12 Direct Method Calls Between Modules

4.13 Dynamic Module Creation

4.13.1 When To Use

4.13.2 Overview

4.13.3 Creating Modules

4.13.4 Deleting Modules

4.13.5 The preDelete() method

4.13.6 Component Weak Pointers

4.13.7 Module Deletion and finish()

4.13.8 Creating Connections

4.13.9 Removing Connections

4.14 Signals

4.14.1 Design Considerations and Rationale

4.14.2 The Signals Mechanism

4.14.3 Listening to Model Changes

4.15 Signal-Based Statistics Recording

4.15.1 Motivation

4.15.2 Declaring Statistics

4.15.3 Statistics Recording for Dynamically Registered Signals

4.15.4 Adding Result Filters and Recorders Programmatically

4.15.5 Emitting Signals

4.15.6 Writing Result Filters and Recorders

5 Messages and Packets

5.1 Overview

5.2 The cMessage Class

5.2.1 Basic Usage

5.2.2 Duplicating Messages

5.2.3 Message IDs

5.2.4 Control Info

5.2.5 Information About the Last Arrival

5.2.6 Display String

5.3 Self-Messages

5.3.1 Using a Message as Self-Message

5.3.2 Context Pointer

5.4 The cPacket Class

5.4.1 Basic Usage

5.4.2 Identifying the Protocol

5.4.3 Information About the Last Transmission

5.4.4 Encapsulating Packets

5.4.5 Reference Counting

5.4.6 Encapsulating Several Packets

5.5 Attaching Objects To a Message

5.5.1 Attaching Objects

5.5.2 Attaching Parameters

6 Message Definitions

6.1 Introduction

6.1.1 The First Message Class

6.1.2 Ingredients of Message Files

6.2 Classes, Messages, Packets, Structs

6.2.1 Classes, Messages, Packets

6.2.2 Structs

6.3 Enums

6.4 Imports

6.5 Namespaces

6.6 Properties

6.6.1 Data Types

6.7 Fields

6.7.1 Scalar fields

6.7.2 Initial Values

6.7.3 Overriding Initial Values from Subclasses

6.7.4 Const Fields

6.7.5 Abstract Fields

6.7.6 Fixed-Size Arrays

6.7.7 Variable-Size Arrays

6.7.8 Classes and Structs as Fields

6.7.9 Non-Owning Pointer Fields

6.7.10 Owning Pointer Fields

6.8 Literal C++ Blocks

6.9 Using External C++ Types

6.10 Customizing the Generated Class

6.10.1 Customizing Method Names

6.10.2 Injecting Code into Methods

6.10.3 Generating str()

6.10.4 Custom-implementation Methods

6.10.5 Custom Fields

6.10.6 Customizing the Class via Inheritance

6.10.7 Using an Abstract Field

6.11 Descriptor Classes

6.11.1 cClassDescriptor

6.11.2 Controlling Descriptor Generation

6.11.3 Generating Descriptors For Existing Classes

6.11.4 Field Metadata

6.11.5 Method Name Properties

6.11.6 toString/fromString

6.11.7 toValue/fromValue

6.11.8 Field Modifiers

7 The Simulation Library

7.1 Fundamentals

7.1.1 Using the Library

7.1.2 The cObject Base Class

7.1.3 Iterators

7.1.4 Runtime Errors

7.2 Logging from Modules

7.2.1 Log Output

7.2.2 Log Levels

7.2.3 Log Statements

7.2.4 Log Categories

7.2.5 Composition and New lines

7.2.6 Implementation

7.3 Random Number Generators

7.3.1 RNG Implementations

7.3.2 Global and Component-Local RNGs

7.3.3 Accessing the RNGs

7.4 Generating Random Variates

7.4.1 Component Methods

7.4.2 Random Number Stream Classes

7.4.3 Generator Functions

7.4.4 Random Numbers from Histograms

7.4.5 Adding New Distributions

7.5 Container Classes

7.5.1 Queue class: cQueue

7.5.2 Expandable Array: cArray

7.6 Routing Support: cTopology

7.6.1 Overview

7.6.2 Basic Usage

7.6.3 Shortest Paths

7.6.4 Manipulating the graph

7.7 Pattern Matching

7.7.1 cPatternMatcher

7.7.2 cMatchExpression

7.8 Dynamic Expression Evaluation

7.9 Collecting Summary Statistics and Histograms

7.9.1 cStdDev

7.9.2 cHistogram

7.9.3 cPSquare

7.9.4 cKSplit

7.10 Recording Simulation Results

7.10.1 Output Vectors: cOutVector

7.10.2 Output Scalars

7.11 Watches and Snapshots

7.11.1 Basic Watches

7.11.2 Read-write Watches

7.11.3 Structured Watches

7.11.4 STL Watches

7.11.5 Snapshots

7.11.6 Getting Coroutine Stack Usage

7.12 Defining New NED Functions

7.12.1 Define_NED_Function()

7.12.2 Define_NED_Math_Function()

7.13 Deriving New Classes

7.13.1 cObject or Not?

7.13.2 cObject Virtual Methods

7.13.3 Class Registration

7.13.4 Details

7.14 Object Ownership Management

7.14.1 The Ownership Tree

7.14.2 Managing Ownership

8 Graphics and Visualization

8.1 Overview

8.2 Placement of Visualization Code

8.2.1 The refreshDisplay() Method

8.2.2 Advantages

8.2.3 Why is refreshDisplay() const?

8.3 Smooth Animation

8.3.1 Concepts

8.3.2 Smooth vs. Traditional Animation

8.3.3 The Choice of Animation Speed

8.3.4 Holds

8.3.5 Disabling Built-In Animations

8.4 Display Strings

8.4.1 Syntax and Placement

8.4.2 Inheritance

8.4.3 Submodule Tags

8.4.4 Background Tags

8.4.5 Connection Display Strings

8.4.6 Message Display Strings

8.4.7 Parameter Substitution

8.4.8 Colors

8.4.9 Icons

8.4.10 Layouting

8.4.11 Changing Display Strings at Runtime

8.5 Bubbles

8.6 The Canvas

8.6.1 Overview

8.6.2 Creating, Accessing and Viewing Canvases

8.6.3 Figure Classes

8.6.4 The Figure Tree

8.6.5 Creating and Manipulating Figures from NED and C++

8.6.6 Stacking Order

8.6.7 Transforms

8.6.8 Showing/Hiding Figures

8.6.9 Figure Tooltip, Associated Object

8.6.10 Specifying Positions, Colors, Fonts and Other Properties

8.6.11 Primitive Figures

8.6.12 Compound Figures

8.6.13 Self-Refreshing Figures

8.6.14 Figures with Custom Renderers

8.7 3D Visualization

8.7.1 Introduction

8.7.2 The OMNeT++ API for OpenSceneGraph

8.7.3 Using OSG

8.7.4 Using osgEarth

8.7.5 OpenSceneGraph/osgEarth Programming Resources

9 Building Simulation Programs

9.1 Overview

9.2 Using opp_makemake and Makefiles

9.2.1 Command-line Options

9.2.2 Basic Use

9.2.3 Debug and Release Builds

9.2.4 Debugging the Makefile

9.2.5 Using External C/C++ Libraries

9.2.6 Building Directory Trees

9.2.7 Dependency Handling

9.2.8 Out-of-Directory Build

9.2.9 Building Shared and Static Libraries

9.2.10 Recursive Builds

9.2.11 Customizing the Makefile

9.2.12 Projects with Multiple Source Trees

9.2.13 A Multi-Directory Example

9.3 Project Features

9.3.1 What is a Project Feature

9.3.2 The opp_featuretool Program

9.3.3 The .oppfeatures File

9.3.4 How to Introduce a Project Feature

10 Configuring Simulations

10.1 The Configuration File

10.1.1 An Example

10.1.2 File Syntax

10.1.3 File Inclusion

10.2 Sections

10.2.1 The [General] Section

10.2.2 Named Configurations

10.2.3 Section Inheritance

10.3 Assigning Module Parameters

10.3.1 Using Wildcard Patterns

10.3.2 Using the Default Values

10.4 Parameter Studies

10.4.1 Iterations

10.4.2 Named Iteration Variables

10.4.3 Parallel Iteration

10.4.4 Predefined Variables, Run ID

10.4.5 Constraint Expression

10.4.6 Repeating Runs with Different Seeds

10.4.7 Experiment-Measurement-Replication

10.5 Configuring the Random Number Generators

10.5.1 Number of RNGs

10.5.2 RNG Choice

10.5.3 RNG Mapping

10.5.4 Automatic Seed Selection

10.5.5 Manual Seed Configuration

10.6 Logging

10.6.1 Compile-Time Filtering

10.6.2 Runtime Filtering

10.6.3 Log Prefix Format

10.6.4 Configuring Logging in Cmdenv

10.6.5 Configuring Logging in Qtenv

11 Running Simulations

11.1 Introduction

11.2 Simulation Executables vs Libraries

11.3 Command-Line Options

11.4 Configuration Options on the Command Line

11.5 Specifying Ini Files

11.6 Specifying the NED Path

11.7 Selecting a User Interface

11.8 Selecting Configurations and Runs

11.8.1 Run Filter Syntax

11.8.2 The Query Option

11.9 Loading Extra Libraries

11.10 Stopping Condition

11.11 Controlling the Output

11.12 Debugging

11.13 Debugging Leaked Messages

11.14 Debugging Other Memory Problems

11.15 Profiling

11.16 Checkpointing

11.17 Using Cmdenv

11.17.1 Sample Output

11.17.2 Selecting Runs, Batch Operation

11.17.3 Express Mode

11.17.4 Other Options

11.18 The Qtenv Graphical User Interface

11.18.1 Command-Line and Configuration Options

11.19 Running Simulation Campaigns

11.19.1 The Naive Approach

11.19.2 Using opp_runall

11.19.3 Exploiting Clusters

11.20 Akaroa Support: Multiple Replications in Parallel

11.20.1 Introduction

11.20.2 What Is Akaroa

11.20.3 Using Akaroa with OMNeT++

12 Result Recording and Analysis

12.1 Result Recording

12.1.1 Using Signals and Declared Statistics

12.1.2 Direct Result Recording

12.2 Configuring Result Collection

12.2.1 Result File Names

12.2.2 Enabling/Disabling Result Items

12.2.3 Selecting Recording Modes for Signal-Based Statistics

12.2.4 Warm-up Period

12.2.5 Output Vectors Recording Intervals

12.2.6 Recording Event Numbers in Output Vectors

12.2.7 Saving Parameters as Scalars

12.2.8 Recording Precision

12.3 Result Files

12.3.1 The OMNeT++ Result File Format

12.3.2 SQLite Result Files

12.3.3 Scavetool

12.4 Result Analysis

12.4.1 Python Packages

12.4.2 An Example Chart Script

12.5 Alternatives

13 Eventlog

13.1 Introduction

13.2 Configuration

13.2.1 File Name

13.2.2 Recording Intervals

13.2.3 Recording Modules

13.2.4 Recording Message Data

13.3 Eventlog Tool

13.3.1 Filter

13.3.2 Echo

14 Documenting NED and Messages

14.1 Overview

14.2 Documentation Comments

14.2.1 Private Comments

14.2.2 More on Comment Placement

14.3 Referring to Other NED and Message Types

14.3.1 Automatic Linking

14.3.2 Tilde Linking

14.4 Text Layout and Formatting

14.4.1 Paragraphs and Lists

14.4.2 Special Tags

14.4.3 Text Formatting Using HTML

14.4.4 Escaping HTML Tags

14.5 Incorporating Extra Content

14.5.1 Adding a Custom Title Page

14.5.2 Adding Extra Pages

14.5.3 Incorporating Externally Created Pages

14.5.4 File Inclusion

14.5.5 Extending Type Pages with Extra Content

15 Testing

15.1 Overview

15.1.1 Verification, Validation

15.1.2 Unit Testing, Regression Testing

15.2 The opp_test Tool

15.2.1 Introduction

15.2.2 Terminology

15.2.3 Test File Syntax

15.2.4 Test Description

15.2.5 Test Code Generation

15.2.6 PASS Criteria

15.2.7 Extra Processing Steps

15.2.8 Error

15.2.9 Expected Failure

15.2.10 Skipped

15.2.11 opp_test Synopsys

15.2.12 Writing the Control Script

15.3 Smoke Tests

15.4 Fingerprint Tests

15.4.1 Fingerprint Computation

15.4.2 Fingerprint Tests

15.5 Unit Tests

15.6 Module Tests

15.7 Statistical Tests

15.7.1 Validation Tests

15.7.2 Statistical Regression Tests

15.7.3 Implementation

16 Parallel Distributed Simulation

16.1 Introduction to Parallel Discrete Event Simulation

16.2 Assessing Available Parallelism in a Simulation Model

16.3 Parallel Distributed Simulation Support in OMNeT++

16.3.1 Overview

16.3.2 Parallel Simulation Example

16.3.3 Placeholder Modules, Proxy Gates

16.3.4 Configuration

16.3.5 Design of PDES Support in OMNeT++

17 Customizing and Extending OMNeT++

17.1 Overview

17.2 Adding a New Configuration Option

17.2.1 Registration

17.2.2 Reading the Value

17.3 Simulation Lifetime Listeners

17.4 cEvent

17.5 Defining a New Random Number Generator

17.6 Defining a New Event Scheduler

17.7 Defining a New FES Data Structure

17.8 Defining a New Fingerprint Algorithm

17.9 Defining a New Output Scalar Manager

17.10 Defining a New Output Vector Manager

17.11 Defining a New Eventlog Manager

17.12 Defining a New Snapshot Manager

17.13 Defining a New Configuration Provider

17.13.1 Overview

17.13.2 The Startup Sequence

17.13.3 Providing a Custom Configuration Class

17.13.4 Providing a Custom Reader for SectionBasedConfiguration

17.14 Implementing a New User Interface

18 Embedding the Simulation Kernel

18.1 Architecture

18.2 Embedding the OMNeT++ Simulation Kernel

18.2.1 The main() Function

18.2.2 The simulate() Function

18.2.3 Providing an Environment Object

18.2.4 Providing a Configuration Object

18.2.5 Loading NED Files

18.2.6 How to Eliminate NED Files

18.2.7 Assigning Module Parameters

18.2.8 Extracting Statistics from the Model

18.2.9 The Simulation Loop

18.2.10 Multiple, Coexisting Simulations

18.2.11 Installing a Custom Scheduler

18.2.12 Multi-Threaded Programs

19 Appendix A: NED Reference

19.1 Syntax

19.1.1 NED File Name Extension

19.1.2 NED File Encoding

19.1.3 Reserved Words

19.1.4 Identifiers

19.1.5 Case Sensitivity

19.1.6 Literals

19.1.7 Comments

19.1.8 Grammar

19.2 Built-in Definitions

19.3 Packages

19.3.1 Package Declaration

19.3.2 Directory Structure, package.ned

19.4 Components

19.4.1 Simple Modules

19.4.2 Compound Modules

19.4.3 Networks

19.4.4 Channels

19.4.5 Module Interfaces

19.4.6 Channel Interfaces

19.4.7 Resolving the C++ Implementation Class

19.4.8 Properties

19.4.9 Parameters

19.4.10 Pattern Assignments

19.4.11 Gates

19.4.12 Submodules

19.4.13 Connections

19.4.14 Conditional and Loop Connections, Connection Groups

19.4.15 Inner Types

19.4.16 Name Uniqueness

19.4.17 Parameter Assignment Order

19.4.18 Type Name Resolution

19.4.19 Resolution of Parametric Types

19.4.20 Implementing an Interface

19.4.21 Inheritance

19.4.22 Network Build Order

19.5 Expressions

19.5.1 Constants

19.5.2 Array and Object Values

19.5.3 Operators

19.5.4 Referencing Parameters and Loop Variables

19.5.5 The typename Operator

19.5.6 The index Operator

19.5.7 The exists() Operator

19.5.8 The sizeof() Operator

19.5.9 The expr() Operator

19.5.10 Functions

19.5.11 Units of Measurement

20 Appendix B: NED Language Grammar

21 Appendix C: NED XML Binding

22 Appendix D: NED Functions

22.1 Category "conversion":

22.2 Category "i/o":

22.3 Category "math":

22.4 Category "misc":

22.5 Category "ned":

22.6 Category "random/continuous":

22.7 Category "random/discrete":

22.8 Category "strings":

22.9 Category "units":

22.10 Category "xml":

22.11 Category "units/conversion":

23 Appendix E: Message Definitions Grammar

24 Appendix F: Message Class/Field Properties

25 Appendix G: Display String Tags

25.1 Module and Connection Display String Tags

25.2 Message Display String Tags

26 Appendix H: Figure Definitions

26.1 Built-in Figure Types

26.2 Attribute Types

26.3 Figure Attributes

27 Appendix I: Configuration Options

27.1 Configuration Options

27.2 Predefined Variables

28 Appendix J: Result File Formats

28.1 Native Result Files

28.1.1 Version

28.1.2 Run Declaration

28.1.3 Attributes

28.1.4 Iteration Variables

28.1.5 Configuration Entries

28.1.6 Scalar Data

28.1.7 Vector Declaration

28.1.8 Vector Data

28.1.9 Index Header

28.1.10 Index Data

28.1.11 Statistics Object

28.1.12 Field

28.1.13 Histogram Bin

28.2 SQLite Result Files

29 Appendix K: Eventlog File Format

29.1 Supported Entry Types and Their Attributes

30 Appendix L: Python API for Chart Scripts

30.1 Modules

30.1.1 Module omnetpp.scave.results

30.1.2 Module omnetpp.scave.chart

30.1.3 Module omnetpp.scave.ideplot

30.1.4 Module omnetpp.scave.utils

30.1.5 Module omnetpp.scave.vectorops

30.1.6 Module omnetpp.scave.analysis

30.1.7 Module omnetpp.scave.charttemplate

1 Introduction¶

1.1 What Is OMNeT++?¶

OMNeT++ is an object-oriented modular discrete event network simulation framework. It has a generic architecture, so it can be (and has been) used in various problem domains:

- modeling of wired and wireless communication networks

- protocol modeling

- modeling of queueing networks

- modeling of multiprocessors and other distributed hardware systems

- validating of hardware architectures

- evaluating performance aspects of complex software systems

- in general, modeling and simulation of any system where the discrete event approach is suitable, and can be conveniently mapped into entities communicating by exchanging messages.

OMNeT++ itself is not a simulator of anything concrete, but rather provides infrastructure and tools for writing simulations. One of the fundamental ingredients of this infrastructure is a component architecture for simulation models. Models are assembled from reusable components termed modules. Well-written modules are truly reusable, and can be combined in various ways like LEGO blocks.

Modules can be connected with each other via gates (other systems would call them ports), and combined to form compound modules. The depth of module nesting is not limited. Modules communicate through message passing, where messages may carry arbitrary data structures. Modules can pass messages along predefined paths via gates and connections, or directly to their destination; the latter is useful for wireless simulations, for example. Modules may have parameters that can be used to customize module behavior and/or to parameterize the model's topology. Modules at the lowest level of the module hierarchy are called simple modules, and they encapsulate model behavior. Simple modules are programmed in C++, and make use of the simulation library.

OMNeT++ simulations can be run under various user interfaces. Graphical, animating user interfaces are highly useful for demonstration and debugging purposes, and command-line user interfaces are best for batch execution.

The simulator as well as user interfaces and tools are highly portable. They are tested on the most common operating systems (Linux, Mac OS/X, Windows), and they can be compiled out of the box or after trivial modifications on most Unix-like operating systems.

OMNeT++ also supports parallel distributed simulation. OMNeT++ can use several mechanisms for communication between partitions of a parallel distributed simulation, for example MPI or named pipes. The parallel simulation algorithm can easily be extended, or new ones can be plugged in. Models do not need any special instrumentation to be run in parallel -- it is just a matter of configuration. OMNeT++ can even be used for classroom presentation of parallel simulation algorithms, because simulations can be run in parallel even under the GUI that provides detailed feedback on what is going on.

OMNEST is the commercially supported version of OMNeT++. OMNeT++ is free only for academic and non-profit use; for commercial purposes, one needs to obtain OMNEST licenses from Simulcraft Inc.

1.2 Organization of This Manual¶

The manual is organized as follows:

- The Chapters [1] and [2] contain introductory material.

- The second group of chapters, [3], [4] and [7] are the programming guide. They present the NED language, describe the simulation concepts and their implementation in OMNeT++, explain how to write simple modules, and describe the class library.

- The chapters [8] and [14]explain how to customize the network graphics and how to write NED source code comments from which documentation can be generated.

- Chapters [9], [10], [11] and [12] deal with practical issues like building and running simulations and analyzing results, and describe the tools OMNeT++ provides to support these tasks.

- Chapter [16] is devoted to the support of distributed execution.

- Chapters [17] and [18] explain the architecture and internals of OMNeT++, as well as ways to extend it and embed it into larger applications.

- The appendices provide a reference on the NED language, configuration options, file formats, and other details.

2 Overview¶

2.1 Modeling Concepts¶

An OMNeT++ model consists of modules that communicate with message passing. The active modules are termed simple modules; they are written in C++, using the simulation class library. Simple modules can be grouped into compound modules and so forth; the number of hierarchy levels is unlimited. The whole model, called network in OMNeT++, is itself a compound module. Messages can be sent either via connections that span modules or directly to other modules. The concept of simple and compound modules is similar to DEVS atomic and coupled models.

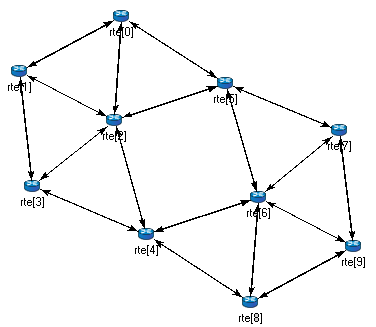

In Fig. below, boxes represent simple modules (gray background) and compound modules. Arrows connecting small boxes represent connections and gates.

Modules communicate with messages that may contain arbitrary data, in addition to usual attributes such as a timestamp. Simple modules typically send messages via gates, but it is also possible to send them directly to their destination modules. Gates are the input and output interfaces of modules: messages are sent through output gates and arrive through input gates. An input gate and output gate can be linked by a connection. Connections are created within a single level of module hierarchy; within a compound module, corresponding gates of two submodules, or a gate of one submodule and a gate of the compound module can be connected. Connections spanning hierarchy levels are not permitted, as they would hinder model reuse. Because of the hierarchical structure of the model, messages typically travel through a chain of connections, starting and arriving in simple modules. Compound modules act like "cardboard boxes" in the model, transparently relaying messages between their inner realm and the outside world. Parameters such as propagation delay, data rate and bit error rate, can be assigned to connections. One can also define connection types with specific properties (termed channels) and reuse them in several places. Modules can have parameters. Parameters are used mainly to pass configuration data to simple modules, and to help define model topology. Parameters can take string, numeric, or boolean values. Because parameters are represented as objects in the program, parameters -- in addition to holding constants -- may transparently act as sources of random numbers, with the actual distributions provided with the model configuration. They may interactively prompt the user for the value, and they might also hold expressions referencing other parameters. Compound modules may pass parameters or expressions of parameters to their submodules.

OMNeT++ provides efficient tools for the user to describe the structure of the actual system. Some of the main features are the following:

- hierarchically nested modules

- modules are instances of module types

- modules communicate with messages through channels

- flexible module parameters

- topology description language

2.1.1 Hierarchical Modules¶

An OMNeT++ model consists of hierarchically nested modules that communicate by passing messages to each other. OMNeT++ models are often referred to as networks. The top level module is the system module. The system module contains submodules that can also contain submodules themselves (Fig. below). The depth of module nesting is unlimited, allowing the user to reflect the logical structure of the actual system in the model structure.

Model structure is described in OMNeT++'s NED language.

Modules that contain submodules are termed compound modules, as opposed to simple modules at the lowest level of the module hierarchy. Simple modules contain the algorithms of the model. The user implements the simple modules in C++, using the OMNeT++ simulation class library.

2.1.2 Module Types¶

Both simple and compound modules are instances of module types. In describing the model, the user defines module types; instances of these module types serve as components for more complex module types. Finally, the user creates the system module as an instance of a previously defined module type; all modules of the network are instantiated as submodules and sub-submodules of the system module.

When a module type is used as a building block, it makes no difference whether it is a simple or compound module. This allows the user to split a simple module into several simple modules embedded into a compound module, or vice versa, to aggregate the functionality of a compound module into a single simple module, without affecting existing users of the module type.

Module types can be stored in files separately from the place of their actual usage. This means that the user can group existing module types and create component libraries. This feature will be discussed later, in chapter [11].

2.1.3 Messages, Gates, Links¶

Modules communicate by exchanging messages. In an actual simulation, messages can represent frames or packets in a computer network, jobs or customers in a queuing network or other types of mobile entities. Messages can contain arbitrarily complex data structures. Simple modules can send messages either directly to their destination or along a predefined path, through gates and connections.

The “local simulation time” of a module advances when the module receives a message. The message can arrive from another module or from the same module (self-messages are used to implement timers).

Gates are the input and output interfaces of modules; messages are sent out through output gates and arrive through input gates.

Each connection (also called link) is created within a single level of the module hierarchy: within a compound module, one can connect the corresponding gates of two submodules, or a gate of one submodule and a gate of the compound module (Fig. below).

Because of the hierarchical structure of the model, messages typically travel through a series of connections, starting and arriving in simple modules. Compound modules act like “cardboard boxes” in the model, transparently relaying messages between their inner realm and the outside world.

2.1.4 Modeling of Packet Transmissions¶

To facilitate the modeling of communication networks, connections can be used to model physical links. Connections support the following parameters: data rate, propagation delay, bit error rate and packet error rate, and may be disabled. These parameters and the underlying algorithms are encapsulated into channel objects. The user can parameterize the channel types provided by OMNeT++, and also create new ones.

When data rates are in use, a packet object is by default delivered to the target module at the simulation time that corresponds to the end of the packet reception. Since this behavior is not suitable for the modeling of some protocols (e.g. half-duplex Ethernet), OMNeT++ provides the possibility for the target module to specify that it wants the packet object to be delivered to it when the packet reception starts.

2.1.5 Parameters¶

Modules can have parameters. Parameters can be assigned in either the NED files or the configuration file omnetpp.ini.

Parameters can be used to customize simple module behavior, and to parameterize the model topology.

Parameters can take string, numeric or boolean values, or can contain XML data trees. Numeric values include expressions using other parameters and calling C functions, random variables from different distributions, and values input interactively by the user.

Numeric-valued parameters can be used to construct topologies in a flexible way. Within a compound module, parameters can define the number of submodules, number of gates, and the way the internal connections are made.

2.1.6 Topology Description Method¶

The user defines the structure of the model in NED language descriptions (Network Description). The NED language will be discussed in detail in chapter [3].

2.2 Programming the Algorithms¶

The simple modules of a model contain algorithms as C++ functions. The full flexibility and power of the programming language can be used, supported by the OMNeT++ simulation class library. The simulation programmer can choose between event-driven and process-style description, and freely use object-oriented concepts (inheritance, polymorphism etc) and design patterns to extend the functionality of the simulator.

Simulation objects (messages, modules, queues etc.) are represented by C++ classes. They have been designed to work together efficiently, creating a powerful simulation programming framework. The following classes are part of the simulation class library:

- module, gate, parameter, channel

- message, packet

- container classes (e.g. queue, array)

- data collection classes

- statistic and distribution estimation classes (histograms, P2 algorithm for calculating quantiles etc.)

The classes are also specially instrumented, allowing one to traverse objects of a running simulation and display information about them such as name, class name, state variables or contents. This feature makes it possible to create a simulation GUI where all internals of the simulation are visible.

2.3 Using OMNeT++¶

2.3.1 Building and Running Simulations¶

This section provides insights into working with OMNeT++ in practice. Issues such as model files and compiling and running simulations are discussed.

An OMNeT++ model consists of the following parts:

- NED language topology description(s) (.ned files) that describe the module structure with parameters, gates, etc. NED files can be written using any text editor, but the OMNeT++ IDE provides excellent support for two-way graphical and text editing.

- Message definitions (.msg files) that let one define message types and add data fields to them. OMNeT++ will translate message definitions into full-fledged C++ classes.

- Simple module sources. They are C++ files, with .h/.cc suffix.

The simulation system provides the following components:

- Simulation kernel. This contains the code that manages the simulation and the simulation class library. It is written in C++, compiled into a shared or static library.

- User interfaces. OMNeT++ user interfaces are used in simulation execution, to facilitate debugging, demonstration, or batch execution of simulations. They are written in C++, compiled into libraries.

Simulation programs are built from the above components. First, .msg files are translated into C++ code using the opp_msgc. program. Then all C++ sources are compiled and linked with the simulation kernel and a user interface library to form a simulation executable or shared library. NED files are loaded dynamically in their original text forms when the simulation program starts.

2.3.1.1 Running the Simulation and Analyzing the Results¶

The simulation may be compiled as a standalone program executable, or as a shared library to be run using OMNeT++'s opp_run utility. When the program is started, it first reads the NED files, then the configuration file usually called omnetpp.ini. The configuration file contains settings that control how the simulation is executed, values for model parameters, etc. The configuration file can also prescribe several simulation runs; in the simplest case, they will be executed by the simulation program one after another.

The output of the simulation is written into result files: output vector files, output scalar files, and possibly the user's own output files. OMNeT++ contains an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) that provides rich environment for analyzing these files. Output files are line-oriented text files which makes it possible to process them with a variety of tools and programming languages as well, including Matlab, GNU R, Perl, Python, and spreadsheet programs.

2.3.1.2 User Interfaces¶

The primary purpose of user interfaces is to make the internals of the model visible to the user, to control simulation execution, and possibly allow the user to intervene by changing variables/objects inside the model. This is very important in the development/debugging phase of the simulation project. Equally important, a hands-on experience allows the user to get a feel of the model's behavior. The graphical user interface can also be used to demonstrate a model's operation.

The same simulation model can be executed with various user interfaces, with no change in the model files themselves. The user would typically test and debug the simulation with a powerful graphical user interface, and finally run it with a simple, fast user interface that supports batch execution.

2.3.1.3 Component Libraries¶

Module types can be stored in files separate from the place of their actual use, enabling the user to group existing module types and create component libraries.

2.3.1.4 Universal Standalone Simulation Programs¶

A simulation executable can store several independent models that use the same set of simple modules. The user can specify in the configuration file which model is to be run. This allows one to build one large executable that contains several simulation models, and distribute it as a standalone simulation tool. The flexibility of the topology description language also supports this approach.

2.3.2 What Is in the Distribution¶

An OMNeT++ installation contains the following subdirectories. Depending on the platform, there may also be additional directories present, containing software bundled with OMNeT++.)

The simulation system itself:

omnetpp/ OMNeT++ root directory

bin/ OMNeT++ executables

include/ header files for simulation models

lib/ library files

images/ icons and backgrounds for network graphics

doc/ manuals, readme files, license, APIs, etc.

ide-customization-guide/ how to write new wizards for the IDE

ide-developersguide/ writing extensions for the IDE

manual/ manual in HTML

ned2/ DTD definition of the XML syntax for NED files

tictoc-tutorial/ introduction into using OMNeT++

api/ API reference in HTML

nedxml-api/ API reference for the NEDXML library

parsim-api/ API reference for the parallel simulation library

src/ OMNeT++ sources

sim/ simulation kernel

parsim/ files for distributed execution

netbuilder/files for dynamically reading NED files

envir/ common code for user interfaces

cmdenv/ command-line user interface

qtenv/ Qt-based user interface

nedxml/ NEDXML library, opp_nedtool, opp_msgtool

scave/ result analysis library, opp_scavetool

eventlog/ eventlog processing library

layout/ graph layouter for network graphics

common/ common library

utils/ opp_makemake, opp_test, etc.

ide/ Simulation IDE

python/ Python libraries for OMNeT++

omnetpp/ Python package name

scave/ Python API for result analysis

...

test/ Regression test suite

core/ tests for the simulation library

anim/ tests for graphics and animation

dist/ tests for the built-in distributions

makemake/ tests for opp_makemake

...

The Eclipse-based Simulation IDE is in the ide directory.

ide/ Simulation IDE

features/ Eclipse feature definitions

plugins/ IDE plugins (extensions to the IDE can be dropped here)

...

The Windows version of OMNeT++ contains a redistribution of the MinGW gcc compiler, together with a copy of MSYS that provides Unix tools commonly used in Makefiles. The MSYS directory also contains various 3rd party open-source libraries needed to compile and run OMNeT++.

tools/ Platform specific tools and compilers (e.g. MinGW/MSYS on Windows)

Sample simulations are in the samples directory.

samples/ directories for sample simulations

aloha/ models the Aloha protocol

cqn/ Closed Queueing Network

...

The contrib directory contains material from the OMNeT++ community.

contrib/ directory for contributed material

akaroa/ Patch to compile akaroa on newer gcc systems

topologyexport/ Export the topology of a model in runtime

...

3 The NED Language¶

3.1 NED Overview¶

The user describes the structure of a simulation model in the NED language. NED stands for Network Description. NED lets the user declare simple modules, and connect and assemble them into compound modules. The user can label some compound modules as networks; that is, self-contained simulation models. Channels are another component type, whose instances can also be used in compound modules.

The NED language has several features which let it scale well to large projects:

- Hierarchical. The traditional way to deal with complexity is by introducing hierarchies. In OMNeT++, any module which would be too complex as a single entity can be broken down into smaller modules, and used as a compound module.

- Component-Based. Simple modules and compound modules are inherently reusable, which not only reduces code copying, but more importantly, allows component libraries (like the INET Framework, MiXiM, Castalia, etc.) to exist.

- Interfaces. Module and channel interfaces can be used as a placeholder where normally a module or channel type would be used, and the concrete module or channel type is determined at network setup time by a parameter. Concrete module types have to “implement” the interface they can substitute. For example, given a compound module type named MobileHost contains a mobility submodule of the type IMobility (where IMobility is a module interface), the actual type of mobility may be chosen from the module types that implemented IMobility (RandomWalkMobility, TurtleMobility, etc.)

- Inheritance. Modules and channels can be subclassed. Derived modules and channels may add new parameters, gates, and (in the case of compound modules) new submodules and connections. They may set existing parameters to a specific value, and also set the gate size of a gate vector. This makes it possible, for example, to take a GenericTCPClientApp module and derive an FTPClientApp from it by setting certain parameters to a fixed value; or to derive a WebClientHost compound module from a BaseHost compound module by adding a WebClientApp submodule and connecting it to the inherited TCP submodule.

- Packages. The NED language features a Java-like package structure, to reduce the risk of name clashes between different models. NEDPATH (similar to Java's CLASSPATH) has also been introduced to make it easier to specify dependencies among simulation models.

- Inner types. Channel types and module types used locally by a compound module can be defined within the compound module, in order to reduce namespace pollution.

- Metadata annotations. It is possible to annotate module or channel types, parameters, gates and submodules by adding properties. Metadata are not used by the simulation kernel directly, but they can carry extra information for various tools, the runtime environment, or even for other modules in the model. For example, a module's graphical representation (icon, etc) or the prompt string and measurement unit (milliwatt, etc) of a parameter are already specified as metadata annotations.

- NOTE

The NED language has changed significantly in the 4.0 version. Inheritance, interfaces, packages, inner types, metadata annotations, inout gates were all added in the 4.0 release, together with many other features. Since the basic syntax has changed as well, old NED files need to be converted to the new syntax. There are automated tools for this purpose, so manual editing is only needed to take advantage of new NED features.

The NED language has an equivalent tree representation which can be serialized to XML; that is, NED files can be converted to XML and back without loss of data, including comments. This lowers the barrier for programmatic manipulation of NED files; for example extracting information, refactoring and transforming NED, generating NED from information stored in other systems like SQL databases, and so on.

- NOTE

This chapter is going to explain the NED language gradually, via examples. A more formal and concise treatment can be found in Appendix [20].

3.2 NED Quickstart¶

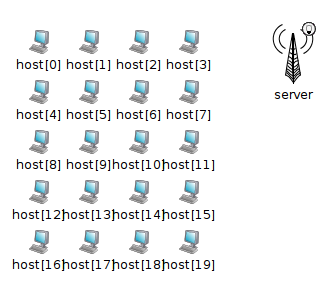

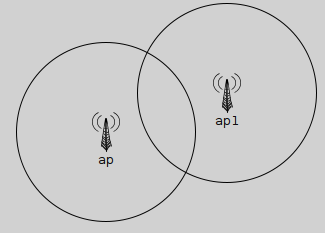

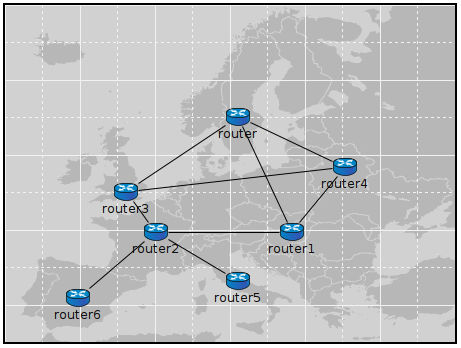

In this section we introduce the NED language via a complete and reasonably real-life example: a communication network.

Our hypothetical network consists of nodes. On each node there is an application running which generates packets at random intervals. The nodes are routers themselves as well. We assume that the application uses datagram-based communication, so that we can leave out the transport layer from the model.

3.2.1 The Network¶

First we'll define the network, then in the next sections we'll continue to define the network nodes.

Let the network topology be as in Figure below.

The corresponding NED description would look like this:

//

// A network

//

network Network

{

submodules:

node1: Node;

node2: Node;

node3: Node;

...

connections:

node1.port++ <--> {datarate=100Mbps;} <--> node2.port++;

node2.port++ <--> {datarate=100Mbps;} <--> node4.port++;

node4.port++ <--> {datarate=100Mbps;} <--> node6.port++;

...

}

The above code defines a network type named Network. Note that the NED language uses the familiar curly brace syntax, and “//” to denote comments.

- NOTE

Comments in NED not only make the source code more readable, but in the OMNeT++ IDE they also are displayed at various places (tooltips, content assist, etc), and become part of the documentation extracted from the NED files. The NED documentation system, not unlike JavaDoc or Doxygen, will be described in Chapter [14].

The network contains several nodes, named node1, node2, etc. from the NED module type Node. We'll define Node in the next sections.

The second half of the declaration defines how the nodes are to be connected. The double arrow means bidirectional connection. The connection points of modules are called gates, and the port++ notation adds a new gate to the port[] gate vector. Gates and connections will be covered in more detail in sections [3.7] and [3.9]. Nodes are connected with a channel that has a data rate of 100Mbps.

- NOTE

In many other systems, the equivalent of OMNeT++ gates are called ports. We have retained the term gate to reduce collisions with other uses of the otherwise overloaded word port: router port, TCP port, I/O port, etc.

The above code would be placed into a file named Net6.ned. It is a convention to put every NED definition into its own file and to name the file accordingly, but it is not mandatory to do so.

One can define any number of networks in the NED files, and for every simulation the user has to specify which network to set up. The usual way of specifying the network is to put the network option into the configuration (by default the omnetpp.ini file):

[General] network = Network

3.2.2 Introducing a Channel¶

It is cumbersome to have to repeat the data rate for every connection. Luckily, NED provides a convenient solution: one can create a new channel type that encapsulates the data rate setting, and this channel type can be defined inside the network so that it does not litter the global namespace.

The improved network will look like this:

//

// A Network

//

network Network

{

types:

channel C extends ned.DatarateChannel {

datarate = 100Mbps;

}

submodules:

node1: Node;

node2: Node;

node3: Node;

...

connections:

node1.port++ <--> C <--> node2.port++;

node2.port++ <--> C <--> node4.port++;

node4.port++ <--> C <--> node6.port++;

...

}

Later sections will cover the concepts used (inner types, channels, the DatarateChannel built-in type, inheritance) in detail.

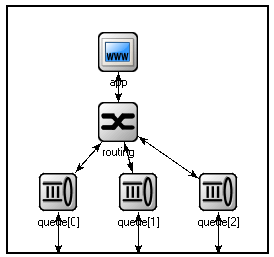

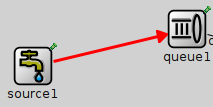

3.2.3 The App, Routing, and Queue Simple Modules¶

Simple modules are the basic building blocks for other (compound) modules, denoted by the simple keyword. All active behavior in the model is encapsulated in simple modules. Behavior is defined with a C++ class; NED files only declare the externally visible interface of the module (gates, parameters).

In our example, we could define Node as a simple module. However, its functionality is quite complex (traffic generation, routing, etc), so it is better to implement it with several smaller simple module types which we are going to assemble into a compound module. We'll have one simple module for traffic generation (App), one for routing (Routing), and one for queueing up packets to be sent out (Queue). For brevity, we omit the bodies of the latter two in the code below.

simple App

{

parameters:

int destAddress;

...

@display("i=block/browser");

gates:

input in;

output out;

}

simple Routing

{

...

}

simple Queue

{

...

}

By convention, the above simple module declarations go into the App.ned, Routing.ned and Queue.ned files.

- NOTE

Note that module type names (App, Routing, Queue) begin with a capital letter, and parameter and gate names begin with lowercase -- this is the recommended naming convention. Capitalization matters because the language is case sensitive.

Let us look at the first simple module type declaration. App has a parameter called destAddress (others have been omitted for now), and two gates named out and in for sending and receiving application packets.

The argument of @display() is called a display string, and it defines the rendering of the module in graphical environments; "i=..." defines the default icon.

Generally, @-words like @display are called properties in NED, and they are used to annotate various objects with metadata. Properties can be attached to files, modules, parameters, gates, connections, and other objects, and parameter values have a very flexible syntax.

3.2.4 The Node Compound Module¶

Now we can assemble App, Routing and Queue into the compound module Node. A compound module can be thought of as a “cardboard box” that groups other modules into a larger unit, which can further be used as a building block for other modules; networks are also a kind of compound module.

module Node { parameters: int address; @display("i=misc/node_vs,gold"); gates: inout port[]; submodules: app: App; routing: Routing; queue[sizeof(port)]: Queue; connections: routing.localOut --> app.in; routing.localIn <-- app.out; for i=0..sizeof(port)-1 { routing.out[i] --> queue[i].in; routing.in[i] <-- queue[i].out; queue[i].line <--> port[i]; } }

Compound modules, like simple modules, may have parameters and gates. Our Node module contains an address parameter, plus a gate vector of unspecified size, named port. The actual gate vector size will be determined implicitly by the number of neighbours when we create a network from nodes of this type. The type of port[] is inout, which allows bidirectional connections.

The modules that make up the compound module are listed under submodules. Our Node compound module type has an app and a routing submodule, plus a queue[] submodule vector that contains one Queue module for each port, as specified by [sizeof(port)]. (It is legal to refer to [sizeof(port)] because the network is built in top-down order, and the node is already created and connected at network level when its submodule structure is built out.)

In the connections section, the submodules are connected to each other and to the parent module. Single arrows are used to connect input and output gates, and double arrows connect inout gates, and a for loop is utilized to connect the routing module to each queue module, and to connect the outgoing/incoming link (line gate) of each queue to the corresponding port of the enclosing module.

3.2.5 Putting It Together¶

We have created the NED definitions for this example, but how are they used by OMNeT++? When the simulation program is started, it loads the NED files. The program should already contain the C++ classes that implement the needed simple modules, App, Routing and Queue; their C++ code is either part of the executable or is loaded from a shared library. The simulation program also loads the configuration (omnetpp.ini), and determines from it that the simulation model to be run is the Network network. Then the network is instantiated for simulation.

The simulation model is built in a top-down preorder fashion. This means that starting from an empty system module, all submodules are created, their parameters and gate vector sizes are assigned, and they are fully connected before the submodule internals are built.

In the following sections we'll go through the elements of the NED language and look at them in more detail.

3.3 Simple Modules¶

Simple modules are the active components in the model. Simple modules are defined with the simple keyword.

An example simple module:

simple Queue

{

parameters:

int capacity;

@display("i=block/queue");

gates:

input in;

output out;

}

Both the parameters and gates sections are optional, that is, they can be left out if there is no parameter or gate. In addition, the parameters keyword itself is optional too; it can be left out even if there are parameters or properties.

Note that the NED definition doesn't contain any code to define the operation of the module: that part is expressed in C++. By default, OMNeT++ looks for C++ classes of the same name as the NED type (so here, Queue).

One can explicitly specify the C++ class with the @class property. Classes with namespace qualifiers are also accepted, as shown in the following example that uses the mylib::Queue class:

simple Queue

{

parameters:

int capacity;

@class(mylib::Queue);

@display("i=block/queue");

gates:

input in;

output out;

}

If there are several modules whose C++ implementation classes are in the same namespace, a better alternative to @class is the @namespace property. The C++ namespace given with @namespace will be prepended to the normal class name. In the following example, the C++ classes will be mylib::App, mylib::Router and mylib::Queue:

@namespace(mylib);

simple App {

...

}

simple Router {

...

}

simple Queue {

...

}

The @namespace property may not only be specified at file level as in the above example, but for packages as well. When placed in a file called package.ned, the namespace will apply to all components in that package and below.

The implementation C++ classes need to be subclassed from the cSimpleModule library class; chapter [4] of this manual describes in detail how to write them.

Simple modules can be extended (or specialized) via subclassing. The motivation for subclassing can be to set some open parameters or gate sizes to a fixed value (see [3.6] and [3.7]), or to replace the C++ class with a different one. Now, by default, the derived NED module type will inherit the C++ class from its base, so it is important to remember that you need to write out @class if you want it to use the new class.

The following example shows how to specialize a module by setting a parameter to a fixed value (and leaving the C++ class unchanged):

simple Queue

{

int capacity;

...

}

simple BoundedQueue extends Queue

{

capacity = 10;

}

In the next example, the author wrote a PriorityQueue C++ class, and wants to have a corresponding NED type, derived from Queue. However, it does not work as expected:

simple PriorityQueue extends Queue // wrong! still uses the Queue C++ class

{

}

The correct solution is to add a @class property to override the inherited C++ class:

simple PriorityQueue extends Queue

{

@class(PriorityQueue);

}

Inheritance in general will be discussed in section [3.13].

3.4 Compound Modules¶

A compound module groups other modules into a larger unit. A compound

module may have gates and parameters like a simple module, but no active

behavior is associated with it.

- [Although the C++ class

for a compound module can be overridden with the @class property,

this is a feature that should probably never be used. Encapsulate the code

into a simple module, and add it as a submodule.]

- NOTE

When there is a temptation to add code to a compound module, then encapsulate the code into a simple module, and add it as a submodule.

A compound module declaration may contain several sections, all of them optional:

module Host

{

types:

...

parameters:

...

gates:

...

submodules:

...

connections:

...

}

Modules contained in a compound module are called submodules, and they are listed in the submodules section. One can create arrays of submodules (i.e. submodule vectors), and the submodule type may come from a parameter.

Connections are listed under the connections section of the declaration. One can create connections using simple programming constructs (loop, conditional). Connection behaviour can be defined by associating a channel with the connection; the channel type may also come from a parameter.

Module and channel types only used locally can be defined in the types section as inner types, so that they do not pollute the namespace.

Compound modules may be extended via subclassing. Inheritance may add new submodules and new connections as well, not only parameters and gates. Also, one may refer to inherited submodules, to inherited types etc. What is not possible is to "de-inherit" or modify submodules or connections.

In the following example, we show how to assemble common protocols

into a "stub" for wireless hosts, and add user agents via

subclassing.

- [Module types, gate names, etc. used in the example

are fictional, not based on an actual OMNeT++-based model framework]

module WirelessHostBase

{

gates:

input radioIn;

submodules:

tcp: TCP;

ip: IP;

wlan: Ieee80211;

connections:

tcp.ipOut --> ip.tcpIn;

tcp.ipIn <-- ip.tcpOut;

ip.nicOut++ --> wlan.ipIn;

ip.nicIn++ <-- wlan.ipOut;

wlan.radioIn <-- radioIn;

}

module WirelessHost extends WirelessHostBase

{

submodules:

webAgent: WebAgent;

connections:

webAgent.tcpOut --> tcp.appIn++;

webAgent.tcpIn <-- tcp.appOut++;

}

The WirelessHost compound module can further be extended, for example with an Ethernet port:

module DesktopHost extends WirelessHost

{

gates:

inout ethg;

submodules:

eth: EthernetNic;

connections:

ip.nicOut++ --> eth.ipIn;

ip.nicIn++ <-- eth.ipOut;

eth.phy <--> ethg;

}

3.5 Channels¶

Channels encapsulate parameters and behaviour associated with connections. Channels are like simple modules, in the sense that there are C++ classes behind them. The rules for finding the C++ class for a NED channel type is the same as with simple modules: the default class name is the NED type name unless there is a @class property (@namespace is also recognized), and the C++ class is inherited when the channel is subclassed.

Thus, the following channel type would expect a CustomChannel C++ class to be present:

channel CustomChannel // requires a CustomChannel C++ class

{

}

The practical difference compared to modules is that one rarely needs to write custom channel C++ class because there are predefined channel types that one can subclass from, inheriting their C++ code. The predefined types are: ned.IdealChannel, ned.DelayChannel and ned.DatarateChannel. (“ned” is the package name; one can get rid of it by importing the types with the import ned.* directive. Packages and imports are described in section [3.14].)

IdealChannel has no parameters, and lets through all messages without delay or any side effect. A connection without a channel object and a connection with an IdealChannel behave in the same way. Still, IdealChannel has its uses, for example when a channel object is required so that it can carry a new property or parameter that is going to be read by other parts of the simulation model.

DelayChannel has two parameters:

- delay is a double parameter which represents the propagation delay of the message. Values need to be specified together with a time unit (s, ms, us, etc.)

- disabled is a boolean parameter that defaults to false; when set to true, the channel object will drop all messages.

DatarateChannel has a few additional parameters compared to DelayChannel:

- datarate is a double parameter that represents the data rate of the channel. Values need to be specified in bits per second or its multiples as unit (bps, kbps, Mbps, Gbps, etc.) Zero is treated specially and results in zero transmission duration, i.e. it stands for infinite bandwidth. Zero is also the default. Data rate is used for calculating the transmission duration of packets.

- ber and per stand for Bit Error Rate and Packet Error Rate, and allow basic error modelling. They expect a double in the [0,1] range. When the channel decides (based on random numbers) that an error occurred during transmission of a packet, it sets an error flag in the packet object. The receiver module is expected to check the flag, and discard the packet as corrupted if it is set. The default ber and per are zero.

- NOTE

There is no channel parameter that specifies whether the channel delivers the message object to the destination module at the end or at the start of the reception; that is decided by the C++ code of the target simple module. See the setDeliverOnReceptionStart() method of cGate.

The following example shows how to create a new channel type by specializing DatarateChannel:

channel Ethernet100 extends ned.DatarateChannel

{

datarate = 100Mbps;

delay = 100us;

ber = 1e-10;

}

- NOTE

The three built-in channel types are also used for connections where the channel type is not explicitly specified.

One may add parameters and properties to channels via subclassing, and may modify existing ones. In the following example, we introduce distance-based calculation of the propagation delay:

channel DatarateChannel2 extends ned.DatarateChannel

{

double distance @unit(m);

delay = this.distance / 200000km * 1s;

}

Parameters are primarily intended to be read by the underlying C++ class, but new parameters may also be added as annotations to be used by other parts of the model. For example, a cost parameter may be used for routing decisions in routing module, as shown in the example below. The example also shows annotation using properties (@backbone).

channel Backbone extends ned.DatarateChannel

{

@backbone;

double cost = default(1);

}

3.6 Parameters¶

Parameters are variables that belong to a module. Parameters can be used in building the topology (number of nodes, etc), and to supply input to C++ code that implements simple modules and channels.

Parameters can be of type double, int, bool, string, xml and object; they can also be declared volatile. For the numeric types, a unit of measurement can also be specified (@unit property).

Parameters can get their value from NED files or from the configuration (omnetpp.ini). A default value can also be given (default(...)), which is used if the parameter is not assigned otherwise.

The following example shows a simple module that has five parameters, three of which have default values:

simple App

{

parameters:

string protocol; // protocol to use: "UDP" / "IP" / "ICMP" / ...

int destAddress; // destination address

volatile double sendInterval @unit(s) = default(exponential(1s));

// time between generating packets

volatile int packetLength @unit(byte) = default(100B);

// length of one packet

volatile int timeToLive = default(32);

// maximum number of network hops to survive

gates:

input in;

output out;

}

3.6.1 Assigning a Value¶

Parameters may get their values in several ways: from NED code, from the configuration (omnetpp.ini), or even, interactively from the user. NED lets one assign parameters at several places: in subclasses via inheritance; in submodule and connection definitions where the NED type is instantiated; and in networks and compound modules that directly or indirectly contain the corresponding submodule or connection.

For instance, one could specialize the above App module type via inheritance with the following definition:

simple PingApp extends App

{

parameters:

protocol = "ICMP/ECHO"

sendInterval = default(1s);

packetLength = default(64byte);

}

This definition sets the protocol parameter to a fixed value ("ICMP/ECHO"), and changes the default values of the sendInterval and packetLength parameters. protocol is now locked down in PingApp, its value cannot be modified via further subclassing or other ways. sendInterval and packetLength are still unassigned here, only their default values have been overwritten.

Now, let us see the definition of a Host compound module that uses PingApp as submodule:

module Host

{

submodules:

ping : PingApp {

packetLength = 128B; // always ping with 128-byte packets

}

...

}

This definition sets the packetLength parameter to a fixed value. It is now hardcoded that Hosts send 128-byte ping packets; this setting cannot be changed from NED or the configuration.

It is not only possible to set a parameter from the compound module that contains the submodule, but also from modules higher up in the module tree. A network that employs several Host modules could be defined like this:

network Network

{

submodules:

host[100]: Host {

ping.timeToLive = default(3);

ping.destAddress = default(0);

}

...

}

Parameter assignment can also be placed into the parameters block of the parent compound module, which provides additional flexibility. The following definition sets up the hosts so that half of them pings host #50, and the other half pings host #0:

network Network

{

parameters:

host[*].ping.timeToLive = default(3);

host[0..49].ping.destAddress = default(50);

host[50..].ping.destAddress = default(0);

submodules:

host[100]: Host;

...

}

Note the use of asterisk to match any index, and .. to match index ranges.

If there were a number of individual hosts instead of a submodule vector, the network definition could look like this:

network Network

{

parameters:

host*.ping.timeToLive = default(3);

host{0..49}.ping.destAddress = default(50);

host{50..}.ping.destAddress = default(0);

submodules:

host0: Host;

host1: Host;

host2: Host;

...

host99: Host;

}

An asterisk matches any substring not containing a dot, and a .. within a pair of curly braces matches a natural number embedded in a string.

In most assigments we have seen above, the left hand side of the equal sign contained a dot and often a wildcard as well (asterisk or numeric range); we call these assignments pattern assignments or deep assignments.

There is one more wildcard that can be used in pattern assignments, and this is the double asterisk; it matches any sequence of characters including dots, so it can match multiple path elements. An example:

network Network

{

parameters:

**.timeToLive = default(3);

**.destAddress = default(0);

submodules:

host0: Host;

host1: Host;

...

}

Note that some assignments in the above examples changed default values, while others set parameters to fixed values. Parameters that received no fixed value in the NED files can be assigned from the configuration (omnetpp.ini).

- IMPORTANT

A non-default value assigned from NED cannot be overwritten later in NED or from ini files; it becomes “hardcoded” as far as ini files and NED usage are concerned.

A parameter can be assigned in the configuration using a similar syntax as NED pattern assignments (actually, it would be more historically accurate to say it the other way round, that NED pattern assignments use a similar syntax to ini files):

Network.host[*].ping.sendInterval = 500ms # for the host[100] example Network.host*.ping.sendInterval = 500ms # for the host0,host1,... example **.sendInterval = 500ms

One often uses the double asterisk to save typing. One can write

**.ping.sendInterval = 500ms

Or if one is certain that only ping modules have sendInterval parameters, the following will suffice:

**.sendInterval = 500ms

Parameter assignments in the configuration are described in section [10.3].

One can also write expressions, including stochastic expressions, in NED files and in ini files as well. For example, here's how one can add jitter to the sending of ping packets:

**.sendInterval = 1s + normal(0s, 0.001s) # or just: normal(1s, 0.001s)

If there is no assignment for a parameter in NED or in the ini file, the default value (given with =default(...) in NED) will be applied implicitly. If there is no default value, the user will be asked, provided the simulation program is allowed to do that; otherwise there will be an error. (Interactive mode is typically disabled for batch executions where it would do more harm than good.)

It is also possible to explicitly apply the default (this can sometimes be useful):

**.sendInterval = default

Finally, one can explicitly ask the simulator to prompt the user interactively for the value (again, provided that interactivity is enabled; otherwise this will result in an error):

**.sendInterval = ask

- NOTE

How can one decide whether to assign a parameter from NED or from an ini file? The advantage of ini files is that they allow a cleaner separation of the model and experiments. NED files (together with C++ code) are considered to be part of the model, and to be more or less constant. Ini files, on the other hand, are for experimenting with the model by running it several times with different parameters. Thus, parameters that are expected to change (or make sense to be changed) during experimentation should be put into ini files.

3.6.2 Expressions¶

Parameter values may be given with expressions. NED language expressions have a

C-like syntax, with additions like quantities (numbers with measurement units,

e.g. 100Gbps) and JSON constructs. Compared to C, there are some

variations on operator names: binary and logical XOR are # and

##, while ^ has been reassigned to power-of instead. The

+ operator does string concatenation as well as numeric addition. There

are two extra operators: <=> (“spaceship”) and =

The spaceship operator <=> compares its two arguments and returns the result (“less”, “equal”, “greater” and “not applicable”) in the form of a negative, zero, positive or nan double number, respectively.

2 <=> 2 // --> 0

10 <=> 5 // --> 1

2 <=> nan // --> nan

The string match operator =

"foo" =~ "f*" // --> true

"foo" =~ "b*" // --> false

"foo" =~ "F*" // --> false

"foo.bar.baz" =~ "*.baz" // --> false

"foo.bar.baz" =~ "**.baz" // --> true

"foo[15]" =~ "foo[5..20]" // --> true

"foo15" =~ "foo{5..20}" // --> true

Expressions may refer to module parameters, gate vector and module vector sizes (using the sizeof operator), existence of a submodule or submodule vector (exists operator), and the index of the current module in a submodule vector (index).

The special operator expr() can be used to pass a formula into a module as a parameter ([3.6.9]).

Expressions may also utilize various numeric, string, stochastic and miscellaneous other functions (fabs(), uniform(), lognormal(), substring(), readFile(), etc.).

- NOTE

The list of NED functions can be found in Appendix [22]. The user can also extend NED with new functions.

3.6.3 Parameter References¶

Expressions may refer to parameters of the compound module being defined, parameters of the current module, and to parameters of already defined submodules, with the syntax submodule.parametername (or submodule[index].parametername).

Unqualified parameter names refer to a parameter of the compound module, wherever it occurs within the compound module definition. For example, all foo references in the following example refer to the network's foo parameter.

network Network

{

parameters:

double foo;

double bar = foo;

submodules:

node[10]: Node {

baz = foo;

}

...

}

Use the this qualifier to refer to another parameter of the same submodule:

submodules:

node: Node {

datarate = this.amount / this.duration;

}

From OMNeT++ 5.7 onwards, there is also a parent qualifier with the obvious meaning.

- NOTE

The interpretation of names which are not qualified with either this or parent and occur within submodule/channel blocks is going to change in OMNeT++ 6.0: An unqualified name foo is going to refer to the parameter of the submodule itself, i.e. will be interpreted as this.foo. To create NED files which are compatible with both versions, make those parameter references explicit by using the parent qualifier: parent.foo. A similar rule applies to the arguments of sizeof and exists.

3.6.4 Volatile Parameters¶

Volatile parameters are those marked with the volatile modifier keyword. Normally, expressions assigned to parameters are evaluated once, and the resulting values are stored in the parameters. In contrast, a volatile parameter holds the expression itself, and it is evaluated every time the parameter is read. Therefore, if the expression contains a stochastic or changing component, such as normal(0,1) (a random value from the unit normal distribution) or simTime() (the current simulation time), reading the parameter may yield a different value every time.

- NOTE

Technically, non-volatile parameters may also contain stochastic values. However, the result of that would be that the simulation use a constant value throughout, chosen randomly at the beginning of the simulation. This is akin to running a randomly selected simulation rather than performing a Monte-Carlo simulation, hence, it is rarely desirable.

If a parameter is marked volatile, the C++ code that implements the corresponding module is expected to re-read the parameter every time a new value is needed, as opposed to reading it once and caching the value in a variable.

To demonstrate the use of volatile, suppose we have a Queue simple module that has a volatile double parameter named serviceTime.

simple Queue

{

parameters:

volatile double serviceTime;

}

Because of the volatile modifier, the C++ code underlying the queue module is supposed read the serviceTime parameter for every job serviced. Thus, if a stochastic value like uniform(0.5s, 1.5s) is assigned the parameter, the expression will be evaluated every time, and every job will likely have a different, random service time.

As another example, here's how one can have a time-varying parameter by exploiting the simTime() NED function:

**.serviceTime = simTime()<1000s ? 1s : 2s # queue that slows down after 1000s

3.6.5 Mutable Parameters¶

A parameter is marked as mutable by adding the @mutable property to it. Mutable parameters can be set to a different value during runtime, whereas normal, i.e. non-mutable parameters cannot be changed after their initial assignment (attempts to do so will result in an error being raised).

Parameter mutability addresses the fact that although it would be technically possible to allow changing the value of any parameter to a different value during runtime, it only really makes sense to do so if the change actually takes effect. Otherwise, users doing the change could be mislead.